This story was originally written just before the death of Dave Achong, founding President of the T&T Surfing Association, and the Rocky Point Foundation’s driving force against the development by Superior Hotels of Mt Irvine’s Rocky Point and Back Bay. Dave is one of the heroes featured in this story of remarkable coincidence in a new novel set in Tobago.

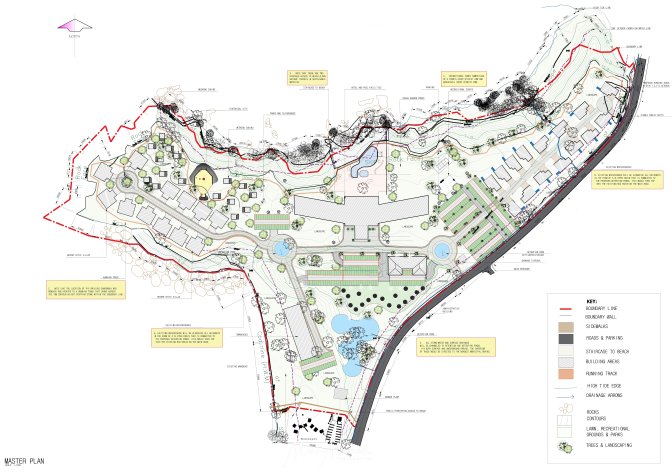

Dave’s passion and drive, fuelled by a wicked sense of humour and delivery, were as unique and irreplaceable as the famous surfing wave which lights up Mt Irvine – which sustained him for so long. Imagine: Rocky Point’s reef and wave destroyed, its wild beauty disappeared beneath concrete, condos, car parks and a multi-storey hotel. It would have been too much for Dave to bear.

Dave once told me, with irrefutable logic, “Who in their right mind would risk the destruction of an asset that costs nothing to create, requires no maintenance, and cannot be replaced?” For all who love Tobago and Mt Irvine, we owe it to Dave to try and Save Rocky Point. So this is for you, for starters, my friend.

“In any other destination in the world, the government of the day would do everything to protect and preserve the attraction. Instead we have a PNM led administration, prepared to give it away, for free, to their financiers, without the consultation of legitimate stakeholders or consultation of even the Tobago people. That development model is a proven failure on Tobago’s landscape, which proves that it is not a resort development, but rather a real estate, land development, with a resort element attached; ergo, a land grab enabled by the prime minister & his administration.”

Dave Achong commenting on the Rocky Point development plans on this blog before the T&T elections. Whether a change of central government will save the day remains to be seen.

PARADISE IN PERIL

The lines between truth and fiction, heroes real and imagined, are entwined amid the mist-draped manchineel and pounding surf of Tobago’s Rocky Point.

BY MARK MEREDITH

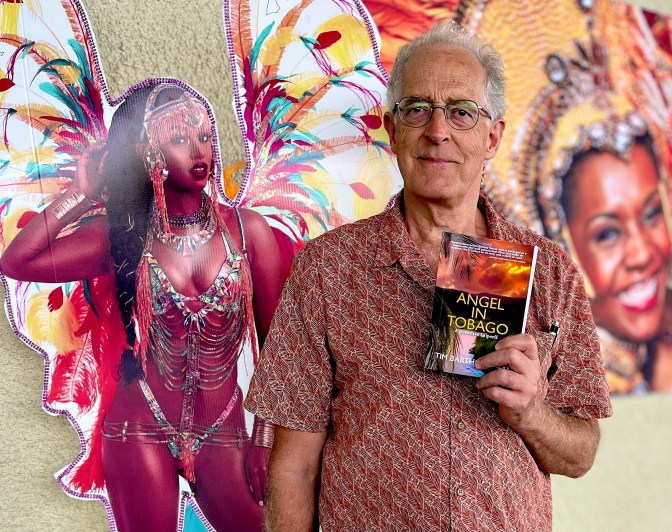

“A stroke of supreme malignant serendipity,” writes Tim Bartholomew in the acknowledgements section of his eco-comedy thriller Angel in Tobago about the real-life threat to Mt Irvine’s Rocky Point.

In a scarcely believable coincidence with current Tobago events, English actor and author Bartholomew launched a fictional book in Tobago in February about a man who battles to save the same unique wilderness at Rocky Point from a hotel development, just as the local community is doing now.

Remarkably though, Bartholomew had no idea of any threat to Rocky Point and its beach, Back Bay, when he sat down to write Angel in Tobago. In it, his hero finds himself struggling to try to save the area from the clutches of a ruthless hotel developer, corrupt officials and bent cops.

News of a Trinidadian hotel company’s advanced plans to build a Marriott-branded hotel with extensive private villas, townhouses and cabanas at the Mt Irvine beauty spot has come as a hugely unpleasant shock to the birdwatching Englishman with a passion for Tobago’s natural history.

His reaction to finding out that the development issues raised in his book were in fact happening in real life in the same place at Rocky Point/Back Bay? “One of utter despondency,” he tells me.

“Six years ago, I plucked my hotel plot line from the scandal of Sandals wanting to build all over the mangroves at Buccoo.

“Angel in Tobago was completed just before this latest ecological horror story began to unfold.”

At the book’s launch he asked incredulously about Rocky Point’s fate: “Why would you destroy the most beautiful beach on the planet?”

His own world-weary answer to that question is: “In my experience, where money – and in my fictionalised version of events, bobol – is involved, mankind will always destroy first and wonder what went wrong afterwards.”

In Angel in Tobago, Gabriel Cassidy, Ghanaian-born but adopted by a white middle-class family in the English Midlands, is sent by his unpleasant adoptive uncle to sell the man’s Tobago estate, called Shurland, to a brash Texan developer – in reality an area set around Rocky Point, Stonehaven Bay and Grafton.

Gabriel, a naive Christian innocent let loose on Tobago for the first time is waylaid by the island’s spirit – Carnival, its tropical colours, landscapes, woods, beaches, birdlife, obeah and bobol.

Without giving too much away, our hero soon realises he has to save Shurland and Rocky Point from the “chainsaws of progress”; that the obvious and logical solution to the developmental threats posed to his fictional estate is to turn it into an ecolodge; a birdwatching, turtle-nesting paradise for nature lovers.

Gabriel vows: “My earthly work must henceforth involve straining every sinew to preserve the beauty, wildlife and mysteries of Shurland’s forest for the future enjoyment and education of hikers, birders and naturalists the world over.”

Which is where the lines between true and fictional heroes weave together like the vines twisting around Back Bay’s manchineel trees.

In the parallel universe of real life, Dave Achong of the Rocky Point Foundation (RPF) wanted nothing more than to see the same outcome as Gabriel envisions but found out the hard way, like Gabriel, that fighting for something you believe in can be a perilous pursuit.

His relentless, unflagging efforts to save Rocky Point cost Achong more than Gabriel – his life. In October 2024, at a crucial and stressful juncture in his campaign, he had a serious heart attack. In March 2025, following a struggle to recuperate, he died.

Achong had been preparing the final stages of what he termed a “genuine public consultation” that RPF was due to host in November at Shaw Park when he was struck down. A number of speakers had been lined up to showcase the many reasons not to cover the land above Back Bay with real estate and a hotel.

The cruel irony is that the fight to save Rocky Point – which had given Achong a brand new lease of life following failing physical health, invigorating him greatly and positively – has repaid his sacrifices by killing him.

If there is a real-life hero in the quest to protect Rocky Point from the “chainsaws of progress” it was surely Dave Achong, 74, founding president of the T&T Surf Association and passionate advocate for Mt Irvine.

Despite being hospitalised in 2017 for a triple heart-bypass operation and then dealing with difficult mobility issues – itself a harsh reality for the veteran pioneer of Mt Irvine’s surf scene – Achong became the central, tireless, galvanising force behind RPF, the NGO set up by surfers opposing the development of Rocky Point. Now they will have to do it without their “warrior”, the “Mayor of Mt Irvine”.

Into the fray has stepped Gabriel Cassidy’s creator Tim Bartholomew, “the accidental activist”, he tells me. Unlike Gabriel, he knows Trinidad and Tobago well; his father-in-law was the famous ornithologist Richard ffrench, who wrote the definitive Birds of Trinidad and Tobago.

Bartholomew, who’s appeared in the BBC’s Doctors, Call the Midwife and Meet the Richardsons, Warner Brothers’ Pennyworth and Sky’s This England (with Kenneth Branagh as Boris Johnson), says of his Tobago introduction, “Like Gabriel, I relished the contrasts, interacted with the locals and became obsessed with photographing its extraordinary bird life.

“I am now irrevocably invested in the ecological wellbeing of Tobago and the welfare of its people, with some of whom I have forged lifelong friendships – and in whose company, like Gabriel, I feel completely at home.”

The timing of Angel in Tobago is prescient, he explains: “In these times of public frustration and anxiety in the face of environmental degradation and self-seeking politicians, I decided to write a deliberately feel-good novel, putting my protagonist through his paces in an authentic Caribbean holiday-escape setting.”

As a tourist destination, Bartholomew believes Tobago “does still have considerable areas of extraordinary beauty which remain relatively unspoilt, untouched and undiscovered” – as per the Tobago Tourism Agency’s advertising. But these points of difference for Tobago “are being encroached upon daily with chunks of forest and hillside being despoiled to accommodate a driveway, a house or whatever”.

He suggests that “what Tobago needs – what the planet needs – are politicians brave enough to ring-fence such areas, like Rocky Point, maybe as reserves for nature, recreation and education”.

But if such “pro-planet politicians” really existed, he says, “they’d need public determination and support behind them to insist upon and fund the redevelopment of brownfield sites such as Arnos Vale and the now mostly empty and rust-stained hotels on Stonehaven Bay below Grafton. Not to mention the Magdalena Hotel, constantly under threat from the sea, oil slicks and weather”.

For Bartholomew, the “blessing of the current government to ‘develop’ Rocky Point in the teeth of environmental objections and despite the majority of hotel bedrooms on the island remaining empty” is profoundly illogical and upsetting. “And don’t start me on how dangerous the beach at Rocky Point is, or how many drownings there are each year…”

Like the ocean current at Back Bay, once it has you in its grip it is hard to break free, just like the hold Rocky Point now has on Bartholomew.

“The usual futile battle is raging in my head. On the one hand, I cling to a shred of optimism about the outcome of the forthcoming Environmental Impact Assessment on those empowered to make decisions. On the other, I remain cynical and utterly pessimistic about the choices the developers and the THA will make.

“My continuing gloom stems from the fact that the developers always come back later – on appeal or otherwise – to have another go when the dust has settled.”

Bartholomew’s pessimism is deepened by his experience of “rubber-stamped” development in the UK, the inexorable loss of England’s green and pleasant countryside despite the best efforts of an “outraged, battle-weary” public.

“In Tobago and other sites in the Caribbean, you have dead coastlines devoid of fish and reefs. Vegetation is cleared only to be replaced with a jungle of half-built hotels in white paint-peeling concrete. True, they boast splendid views of blue seas and sky, but the wildlife and all that sustains it, and us, is gone,” he laments.

“It remains to be seen whether any of Tobago’s natural beauty, forest and wildlife will still exist in 20 years. My personal fear is that, as has happened in several other Caribbean territories, the island and its people will be sold out to the developers: truly a paradise in peril.”

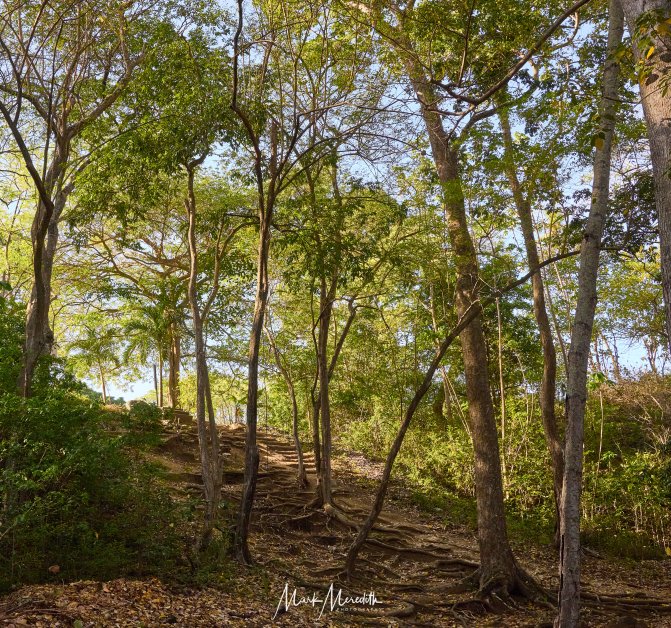

Here are some photos of Back Bay and Rocky Point, the paradise Dave and Gabriel were fighting to save – click on the image for full size

“Of all Tobago’s natural biohazards manchineel is the most toxic and deadly,” he told me. “Every facet of this tree is deadly and seriously poisonous, from its bark, leaves, roots, fruit, and the latex- like oil that emerges from the slightest touch. No creature lives within its space, no birds, ants, spiders, animals, crabs. It is totally incompatible with human interaction or habitation of any sort, whether residential, commercial, or a resort.”